In this fifth guest blog, in our series of viewpoints on the physical and clinical mental health divide, Dr Paul Turner, General Practitioner at Karis Medical Centre, Birmingham and Joint Clinical Director for Mental Health, NHSE West Midlands Clinical Network describes the cost of untreated complexity.

In the first blog of this series Professor Sir Muir Gray succinctly describes the interdependency between mind and body as “warp and weft”; like indivisible fibres of fabric and challenges us to unify the services that have been separated for decades.

Much earlier, Julian Tudor Hart wrote “The availability of good medical care tends to vary inversely with the need for it in the population served. This inverse care law operates more completely where medical care is most exposed to market forces…” (1)

Whilst the context and times in which he wrote were different, the central message still rings true: there exists a “forgotten majority” of people with complex mental distress, often trauma-related, for whom our silos of thinking and care allow gaping holes in and between medical and social services to persist.

Without undermining the considerable investment and advances in the care of people with mental health problems in this country, people experiencing distress continue to fall through gaps on a daily basis. Almost as though our services are patches in a quilt which have not been sewn together. In order that, together, we can make collaborative and creative changes which unify our approach to these people, it is vital that we know the true extent of their need.

In short, we need to start counting complexity

Whilst human expressions of suffering do not distinguish between mind and body - we manifest our distress in the manner which circumstances allow - most of our services continue to do so unflinchingly. One consequence of this is that we undervalue listening and understanding what has happened to a person as we focus on what is “wrong’ with them. This disproportionately affects the people who don’t fit into our paradigm of intervention- based services, and yet who often suffer the most.

Here are some of the consequences of such gaps:

- One out of every 2 people referred by their GP to a new outpatient appointment with persistent physical symptoms, will not be found to have a physical cause for their problem. (2)

- 2/3rds of people who present in mental distress do not find their needs being met. (3)

- 70% of people who take their own lives have seen their GP in the previous year but only 8% were referred to specialist mental health services. (4)

- Antidepressant prescribing has doubled in the last 10 years (mainly long-term prescribing). (5)

- Chronic pain prescribing (particularly gabapentinoids and opioids) continues to escalate, whilst recognition of the near-universal impact of underlying adverse childhood experiences in this group is scant (See Dr Paul Roberts blog in this series).

Just sit back and think for a moment or two about these anomalies in our health care. Bold and brave as the Five Year Forward View for mental health was, it was not designed to answer these questions. Existing funded provision for helping people manage their distress is mainly focussed through local interpretations of the Improving Access to Psychological Services (IAPT) programme and specialist mental health services. However only about one in four people referred to IAPT will recover and the large majority of people referred to specialist mental health services are not offered a service.

Just as IAPT does not purport to solve all psychological problems, neither should we expect specialist mental health care to manage all complexity. Another approach is needed - But what else is there? It is not enough to hope that people will be “signposted to the Third Sector”. Neither is it reasonable that large numbers of people continue to present in mental distress to A&E, whilst Police, Ambulance and Fire Service staff are increasingly involved in supporting people with complex care needs because health services can’t cope.

The NHS Long Term Plan paves the way for considerable re-imagining, embedding and sustaining primary mental health care with the development of collaborative primary care based services, but in order to really ensure that people don’t continue to fall through gaps in care and support, we need to be able to define more clearly who these people are rather than only stocktaking our successes.

The considerable evidence of the benefit of collaborative care in Mental Health, extensively research by Professor Linda Gask and others, has been overlooked as we favour a competitive target-driven approach to flourish (6). Commissioning for collaboration may require us to develop new approaches.

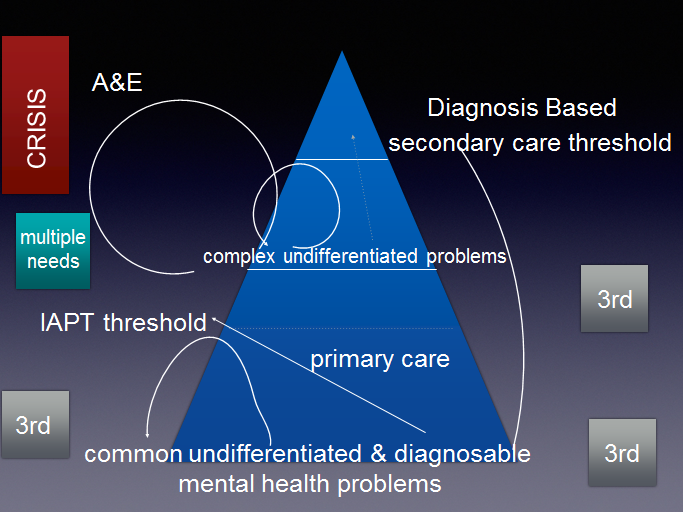

Unsupported, or inadequately supported, people are often given treatment or undergo repeated investigations that do not help, leaving them, their families and their clinicians feeling disappointed, powerless and stressed. The figure below illustrates what happens when people with a range of undifferentiated problems don’t meet threshold for care.

Thresholds are perfectly reasonable, it is equally reasonable to appreciate what they mean for complex human beings.

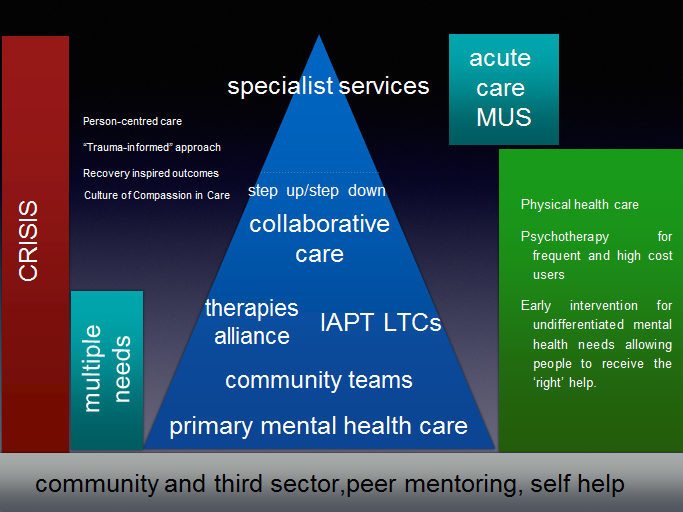

Figure 1 illustrates how people who don’t meet service thresholds in a disjointed system can fall through gaps, circling in and out of care which is not designed to meet their need. (3rd refers to voluntary & charitable sector organisations; MUS refers to medically unexplained (or persistent physical) symptoms.)

Figure 2 suggests how this could be different in a collaborative system where the complex psychosocial factors in peoples’ lives are recognised and addressed more effectively.

Sharing problems, solutions and successes is the essence of effective community, coupled with the collective accountability to identify them. Our framing of the scale of the task is thwarted by only counting (and thus being accountable for) the people we think we can provide interventions for. The complex human distress confronted by Patients, families and frontline clinicians doesn’t afford us such luxury.

The West Midlands Strategy Unit are currently in the process of collating regional data to attempt to define those people affected by gaps in mental health provision. How differently could we provide patient and family centred care in integrated care systems if we collectively also counted those whom we currently cannot offer an adequate service?

In one of his earliest speeches as chief executive of NHS England (7); Simon Stevens said:

“together we’re going to need to work in coherent and purposeful partnership, because the national leadership of the NHS has to be more than the sum of its parts.

The alternative, to quote Milton’s Paradise Lost: ‘Thus they in mutual accusation spent/The fruitless hours…And of their vain contest appeared no end.’ Given everything facing us, we don’t have fruitless hours to waste, and we can’t afford vain contests. Said less poetically, it’s time to roll up our sleeves, pull together, and get on with it.

The health care system that can solve-for the really big challenges – dementia, obesity, inequalities, mental health and wellbeing, personalisation, prevention and empowerment – that’s the health system that will prosper in the 21st century.”

Examples of creative joint working using all the skills and tools at our disposal abound, but they are still at the margins of health policy and commissioning. Insanity, as Albert Einstein famously intoned, is “doing the same thing in the same way and expecting different results”.

Now there’s a diagnosis which really needs treatment.

[2] Bermingham. 4 Bermingham, S.L., Cohen, A., Hague, J., & Parsonage, M. (2010) The cost of somatisation among the working-age population in England for the year 2008- 2009. Mental Health in Family Medicine, 7(2): pp71-84.

[3] Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey: Mental Health and Wellbeing, England, 2014. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/adult-psychiatric-morbidity-survey-mental-health-and-wellbeing-england-2014

[4] Suicide in primary care in England: 2002-2011. National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness (NCISH). Manchester: University of Manchester 2014.

[5] https://digital.nhs.uk/news-and-events/news-archive/2017-news-archive/antidepressants-were-the-area-with-largest-increase-in-prescription-items-in-2016 accessed 26/2/2019

[6] Gask L How can we work more effectively across the interface between psychiatry and primary care? Systematic Review 2017