How well do we understand changing expectations and implications for the NHS?

Rising public expectations are described in the 10 Year Plan as a major factor shaping healthcare of the future. But how are expectations changing? And what are the implications for the NHS?

In a complex system like healthcare, public expectations affect perceptions and behaviours in ways that aren’t entirely predictable. Expectations have the potential to impact demand for healthcare and the success of initiatives to manage demand.

expectation

[ek-spek-tey-shuhn] noun

- a personal or collective belief about a future state, formed from what we know and experience.

- can be conscious or unconscious

- can be specific (beliefs about probable treatment outcomes) or general (what good access to healthcare looks like).

- “the mental picture that patients or the public will have of the process of interaction with the system” (Lateef, 2011)

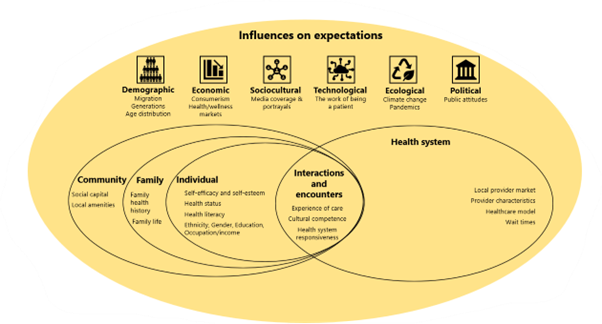

For such an important driver of healthcare demand and utilisation, there are surprisingly few overviews. Whilst there does seem to be consensus that expectations matter, there’s little empirical data. We simply don’t know enough about a phenomenon that has such an important influence on demand and utilisation. But we can draw on theory from sociology, psychology and healthcare to better understand how expectations form and what factors might contribute to changing expectations.

Research tells us that our expectations are dynamic, constantly adjusting in response to our environment. Our individual and collective expectations both shape and are shaped by our experiences: “no expectations without experience; no experience without expectation”. And not just in healthcare but our experiences in everyday life (shopping, banking, socialising) will shape what we expect of our public services. These services play a role too, shaping our horizon of expectation through their actions, processes and policies.

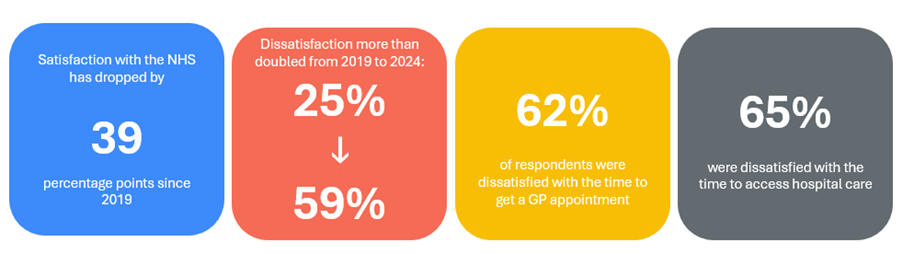

We have a good sense of how public perceptions of the NHS are changing, thanks to the annual British Social Attitudes Survey. The latest results show that public satisfaction is dropping:

But whether or not expectations will also drop isn’t clear yet. On entering Government, the Secretary of State for Health gained significant attention when he described the NHS as “broken”. A subsequent poll by Ipsos suggested that while people who were familiar with this statement did report changed expectations or behaviours, concern for the NHS was more widespread and may have already been impacting how people were engaging with the NHS. There’s some speculation however, that the choice of language could undermine public trust. But without better data, we can’t really know the impact.

It may be that other forces maintain or even raise expectations. Recent polls by the Health Foundation (published in 2024, 2025) suggest a mixed picture of how NHS services are expected to perform in future. The British Social Attitudes survey has shown consistent support for the NHS model in recent years. The NHS has been described as “an idea as well as an institution” which suggests expectations of equity and fairness. But there may be signs that expectations may be changing – more people are buying private healthcare for example. Polling suggests a drop in support for the NHS model though estimates vary. The Health Foundation reports a fall in support for the NHS being free at the point of delivery, from 89% in 2021 to 86% in 2025. Whereas the British Social Attitudes Survey reported a drop in the percentage of people saying the NHS should ‘definitely’ be available to everyone from 67% in 2023 to 56% in 2024.

Rising public expectations are often referenced as a stimulus for change in the NHS but seldom with any real detail, let alone data. The 10-Year Plan does a little unpacking, suggesting how expectations may be changing in terms of convenience, choice and continuity. It’s not explicit but one might assume this is at least partly based on findings from the NHS Change public consultation.

Let’s take digital transformation: the 10-Year Plan is bold and ambitious. There does seem to be a general expectation of a more technology-driven NHS. But there’s a potential mismatch of expectations on the “work of being a patient” between policymakers, providers and patients themselves. As digital technologies become more pervasive, and care shifts beyond hospital and facility walls, expectations of patients and carers become less visible. Recent poll results which hint at diverging expectations of the role of humans and technology in healthcare warrant closer examination.

If we’re going to achieve and sustain improved outcomes, we really need to dig deeper. We should be making a concerted effort to measure expectations directly, robustly and routinely. In particular, the interaction between inequities and expectations given that expectations and experience are so interlinked. We just don’t know enough about how expectations might vary across different communities, geographies and generations.

All this suggests a question: how proactive should politicians, policymakers, commissioners and providers be in shaping expectations? To what extent can, or should, the NHS calibrate expectations? The NHS Constitution, to an extent, sets out what the public can expect of the NHS but awareness is relatively low and aside from a “commitment to innovation”, there’s little to suggest the scale or pace of this change.

If we are going to improve our knowledge of patient expectations, a good place to start would be some research, across different populations, on expectations of the three big shifts (analogue to digital; hospital to community; treatment to prevention), how these vary and how they might be changing. Without a better grasp, unmet expectations may end up driving demand in ways we don’t understand, risking further inequities in access and outcomes.