In 2010, Primary Care Trusts faced a difficult choice. The Transforming Community Services policy required a complete break of commissioner and provider functions, impacting on the jobs and working lives of thousands of staff and the day to day care for millions. But what should PCTs do with the community health services they delivered but now had to give up: vertically integrate with an acute trust, horizontally integrate with a mental health trust, or set up a stand-alone community trust or Community Interest Company? There were powerful advocates for each.

Now the NHS is again looking at models for integration, it seemed to us important to try to understand the consequences of the choices then made. This seemed to be the least that one would want to know on the back of such a huge and significant national change programme. But could we find any systematic national evaluation, any serious attempt to assess whether TCS delivered some of what its policy making architects claimed for it? No….so we decided to look ourselves. And our findings are now available.

The TCS story….and an outbreak of ‘déjà vu’

Our paper sets the scene with a potted account of the context and the key policy issues of the day in and around 2010. The drive for separation, driven by a belief in the power of choice and competition to drive improvement, was stated by policy makers to be of fundamental importance, critical to achieving a new NHS order that they envisaged (but that, 8 years later, has not yet come to pass). Looking back on it now, the degree of certainty exhibited in the many statements about what TCS would achieve looks perhaps cavalier.

‘The NHS will meet its quality and productivity challenge in large part by building and accelerating the momentum for Transforming Community Services, increasingly focusing on prevention and early intervention, achieving an unprecedented transfer of care and treatment from hospital to community settings, and accelerating service integration’

Letter from the Director General Commissioning & System Management to SHA Chief Executives, 5/2/2010, gateway 13527

Reading the archives from this era brought back for those of us who were there at the time the intensity and significance of the TCS change programme for the NHS at the turn of the last decade. TCS was ubiquitous; it was talked about and driven with the same intensity as we see now for ICSs. The land was full of those with ambition espousing the new language with the zeal of the newly converted (an enduring NHS characteristic). A quick scan of the key policy documents and requirements issued to the system shows a certainty amongst policy makers that TCS was ‘the change’ that would make the difference in delivering innovative and integrated local care; and a certainty that it would bring about reduced emergency referrals (and indeed was critical for that).

Now we all know that each iteration of national NHS leadership settles on new policy certainties, often quickly forgetting what has gone before, often not wanting to really understand the lessons learned from that ( R.I.P World Class Commissioning; Darzi reviews; Care Trusts; etc etc) And yet there were times reading the TCS archives where whole paragraphs could have been lifted and shifted into current communications about ICSs…..and the current repetition of the same assurance processes, the same ‘maturity indices’, the same industry of ‘sign off’ of plans led by regional officials was spookily ‘groundhog day’ in effect. When we love to plot our futures forward in brave leaps of soviet-like ‘5 year plans’, 8 years ago should surely feel like a very different place? But actually, no, it was remarkably and maybe disappointingly similar….a lesson in the asymmetry of past and future maybe?

The results

Our work tries to test out empirically the effects of changes (TCS) about which emphatic and definitive things were claimed at the time by policy makers.

It explores the impact the TCS integration choice had on the level and growth in emergency hospital use in older people (a primary outcome that was promised for TCS) and does this in order to consider the wider implications for the NHS as it develops new models of care and integrated care systems. Our analysis suggests that decisions taken in 2010/11 to structurally integrate community nursing services and the form of this integration, vertical or horizontal, did not systematically and differentially influence the rate of emergency hospital admissions of older people. Whilst a positive finding in favour of one approach might have been more striking, our result is still highly informative. It suggests that time consuming and costly mergers and organisational changes should not be confidently promoted or pursued as a means of reducing hospital activity. Other factors appear to be far more significant and more effort should be applied nationally to identifying those critical ingredients robustly rather than anecdotally. If organisational change must take place, then healthcare systems should have other compelling reasons for doing so.

In this respect our analysis supports the permissive approach set out in the Five Year Forward View, allowing local healthcare systems the freedom to develop their own approach of partnership working. It is important that that is sustained despite the temptation to jump to a blueprint and that there is a more systematic and transparent approach to securing high quality evaluation that is openly shared.

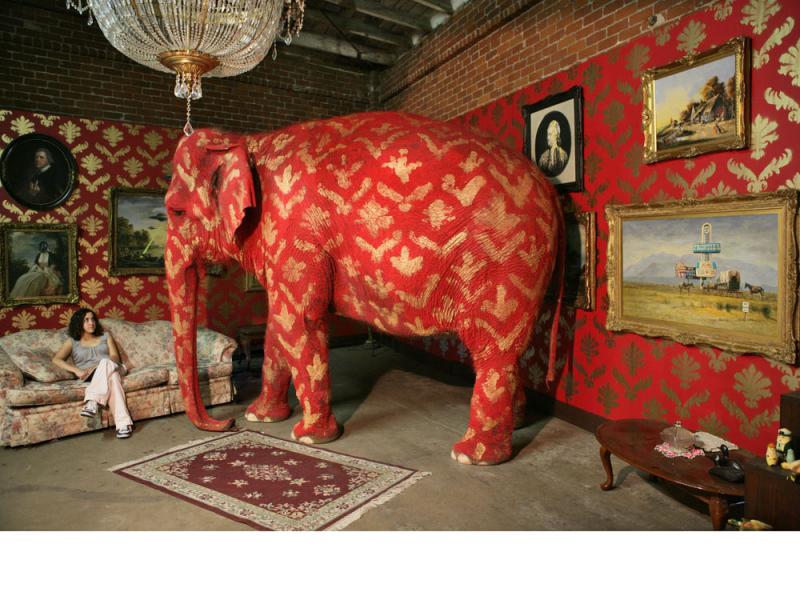

The elephant in the room…?

But the other question left hanging as a result of doing this work, one we didn’t really set out to address at the start, is about the accountability of policy makers. Implementation of TCS, whilst not costed as far as we are aware, was clearly hugely expensive in terms of both actual costs but also in terms of ‘opportunity costs’. There were entire teams dedicated to it for over a year at national, regional and local levels and external consultancies were advising on contractual and organisational forms throughout. Is it unreasonable to argue that if policy makers wish to make definitive claims for what are in reality hypotheses, if they claim that doing x will result in y , …then we might reasonably expect , when the change is scaled in thousands of staff and millions of patients, that this is properly measured , assessed and learnt from?

In an enterprise the scale of the NHS, a senior official can commit £millions on kicking off nation-wide processes at the flick of a pen. It is just too easy to spend vast sums. But when this is public money, the NHS has a duty to be a learning organisation, seeking to build improvement on the back of both successes and failures properly understood. We surely need a culture of policy -maker accountability and open evaluation of national initiatives. The New Models of Care initiative started well in that regard, with at least an intention to create an exercise in controlled experimentation, designed to generate learning from local initiative in response to national instigation. But In that light, the essential value of the NMC programme has to be in that learning. With purportedly £100 million invested in the Vanguards, then expectations of the quality, depth and integrity of that learning, and of its accessibility, should be set very high. How that learning is then translated soberly and without spin into the next stage of the NHS’ journey into integration is the critical test.