Last year marked the 50th anniversary of Julian Tudor Hart’s famous Lancet paper, The Inverse Care Law. The law states that “the availability of good medical or social care tends to vary inversely with the need of the population served”.i Tudor Hart pointed out that these effects were most strongly expressed when access to health care is dictated by an individual’s ability to pay, but are present even in fully insured systems such as the NHS.

A rigorous demonstration of this effect was published 40 years later in the BMJ.ii Andy Judge and colleagues showed that, having adjusted for need, people living in the wealthiest areas in 2002 were more than three times as likely to receive an NHS-funded hip replacement than their counterparts living in the most deprived areas.

Successive governments have pledged to reduce inequalities in health and inequities in access to health services. So we might expect that the inequities, highlighted by Judge, would have been addressed or at least moderated in the intervening period.

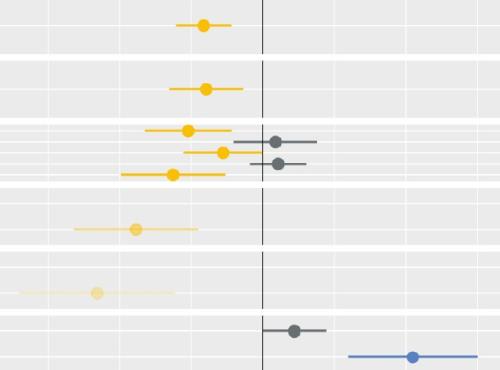

And yet, our recent publication found no evidence that these substantial inequities had improved in either England or Wales.

Our paper was published in the Lancet (Regional Health Europe) and was a collaboration with colleagues from the Royal Orthopaedic Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, and the universities of Swansea and Bristol. We explored whether inequities in access to NHS-funded hip replacements improved between 2006 and 2016.iii

This is just one analysis, but the evidence of persistent inequities in access to healthcare is overwhelming, maybe now undeniable. Indeed, some papers have suggested that access to NHS services became even more inequitable during the pandemic.iv

Has the time has come to adopt more potent and direct strategies to address this issue? Should, for example, payment mechanisms be aligned with our policy objectives, so that providers working with under-supplied populations receive higher payments? Perhaps access to funds to tackle the growing waiting list should be dependent on reducing inequities?

Whatever we choose to do, we can be fairly sure that continuing with existing approaches alone, is unlikely to bring about the change that’s needed.

i https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(71)92410-X

ii https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c4092

iii https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100475

iv https://www.midlandsdecisionsupport.nhs.uk/knowledge-library/strategies…;