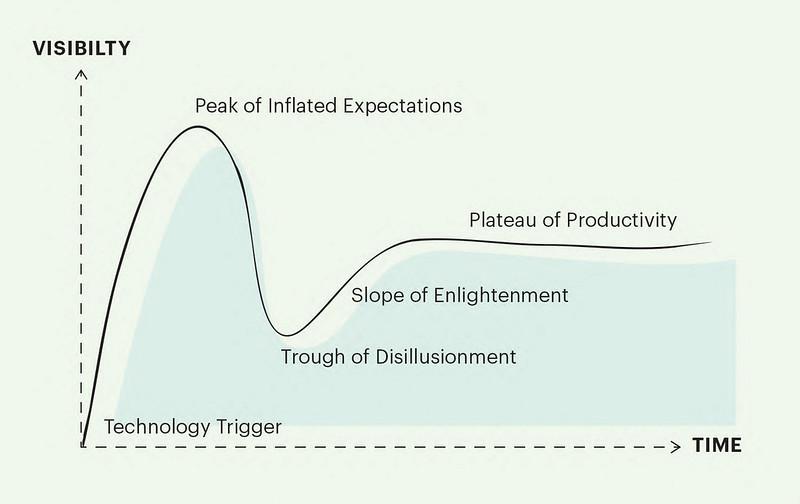

The first effect of policy is on expectations. In every case I can think of, the effect is inflationary. And policies created on the promise that payments can be linked to outcomes are a stand-out example. In this case, the hype – delivery gap is more like a tectonic chasm.

It’s difficult to be precise, but the decade after the election of the Coalition Government in 2010 probably saw the peak of enthusiasm for policies based on this approach.

Programmes came with different labels: Payment by Results (not to be confused with the NHS ‘PbR’ scheme); Outcomes Based Commissioning; Results Based Financing; Social Impact Investing; Pay for Success; (etc). And initiatives mushroomed across the policy landscape: appearing in supported housing, foreign aid, prisoner rehabilitation, unemployment, locating illegal immigrants, (etc).

The fever of the times is captured nicely in a 2010 ‘think piece’ from advisory and audit firm, KPMG:

“Payment by results should be implemented across the public sector without exception… Where payment by results exists it should be made enhanced and where it does not exist it should be hurried into existence, even if it is crude to start with.”

The fever didn’t catch quite as widely as KPMG hoped. But crude hurry certainly did take hold – and at sufficient pace that evidence from evaluation would never catch up.

The NHS was not immune. And over time examples began to emerge where the promise of paying providers for outcomes was failing real world tests.

Often under the guise of ‘Capitated Outcome-Based Incentivised Contracts’ (or COBICs), procurements stalled, contracts were suspended or altered, investigations were ordered, and lessons were noted. Policy hopes were dashed on the delivery rocks of Staffordshire, Cambridgeshire and Peterborough, Oxfordshire, Bedfordshire, Sussex and elsewhere. Policy ideas never quite die. But outcome-based commissioning looked very badly wounded. Why? Because the whole enterprise was doomed from the outset?

High profile and expensive failures will have as many explanations as denials. Lessons from schemes noted here are in various evaluation and official ‘having recovered the flight recorder’ type reports. This isn’t the place to rehearse these details.

Instead, my rough and broad explanation is that what seems intuitively so obvious – that people should be incentivised and rewarded according to the results they achieve – is astonishingly difficult to achieve in practice.

One clue as to why this might be so is in the very word ‘outcome’, which my dictionary has as ‘something that follows as a result or consequence’. It is here that the rocks begin to show. We must be making a causal claim: a result occurs because of an action.

At this point, anyone with a background in evaluation is starting to shrink slightly. We can wish this problem away - or even ignore it altogether - but if we lose sight of the causal link between action and outcome, then talk of ‘results’ becomes increasingly meaningless.

This was where many schemes seemed to unravel. In this case, it seemed that crude beginnings were causally linked to sticky endings.

I'd like to think the Strategy Unit is fairly immune to hype. Our contribution to these debates will always be rooted in careful analytical work. So is it possible to accept all the analytical challenges that come with outcome-based commissioning and still make use of it? Or is it time to abandon hope (until the next time)?

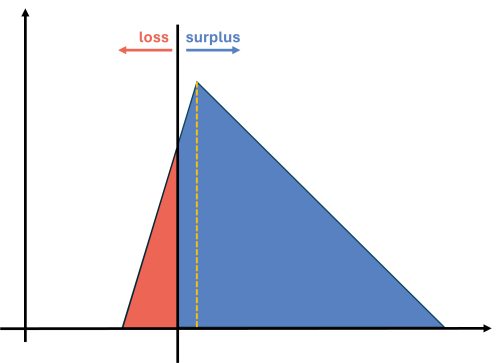

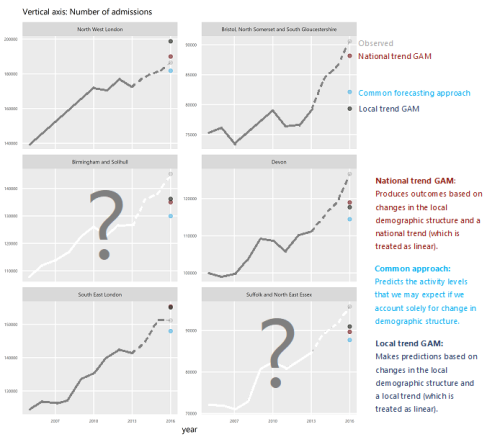

We think hope can be rescued from the rubble of hype. And two of our contributions seem valuable to me. The first, looking at risk and reward sharing for Integrated Care Systems, sets out a route to realising the benefits of such arrangements, while navigating inherent analytical and contractual complexities. The second builds on this and examines the use of risk and reward to incentivise system-level reductions in emergency activity.

And now, following work with Luigi Siciliani (University of York) and Matthew Revell (The Royal Orthopaedic Hospital NHS Foundation Trust), we provide a detailed look at how payments could be structured to incentivise providers to increase the quality of elective knee-replacement surgery.

The report comprehensively fails the hype test. It is a careful and forensically-reasoned piece of work that goes from basic concept (why do this?) up to contractual conditions (how?).

But perhaps this is what’s needed? If outcome-based commissioning is ever to fulfil its promise, maybe it needs saving from its promoters. If this policy is ever going to make it out of the Trough of Disillusionment, then maybe it needs an empirical hand more than a hypeman.