It may be tempting to consider the blended payment system as a technical tool for determining the allocation of resources between commissioners and providers - something that can be left to analysts and finance specialists to negotiate. But the implications of the blended payment system are far reaching: Decisions about planned activity levels will determine the total funding envelope for urgent care within a system and will influence the behaviour of healthcare providers and the services they deliver to patients. This is an unusual situation where senior managers in commissioner and provider organisations must engage in the detail, however esoteric it may seem, to ensure both the financial sustainability of their organisations and the quality and accessibility of services for the populations they serve.

For most NHS services, healthcare commissioners pay providers according to the rules and prices of the National Tariff Payment System (NTPS). Until April 2019, the NTPS operated on a fee-for-service basis. At face value, the fee-for-service model appears to offer providers an incentive to increase supply and therefore sets the financial sustainability of providers against that of the health system as a whole.

It is believed that such tensions might be resolved with the introduction of risk-and-reward-sharing, or “blended payment”, schemes. This alternative payment model encourages the provider to moderate growth in activity by assigning them a share of the annual savings or the cost over-runs. The risk-reward sharing model is currently seen as the most appropriate way to distribute resources in the healthcare system and, as a consequence, the NTPS has recently adopted blended payments for emergency activity.

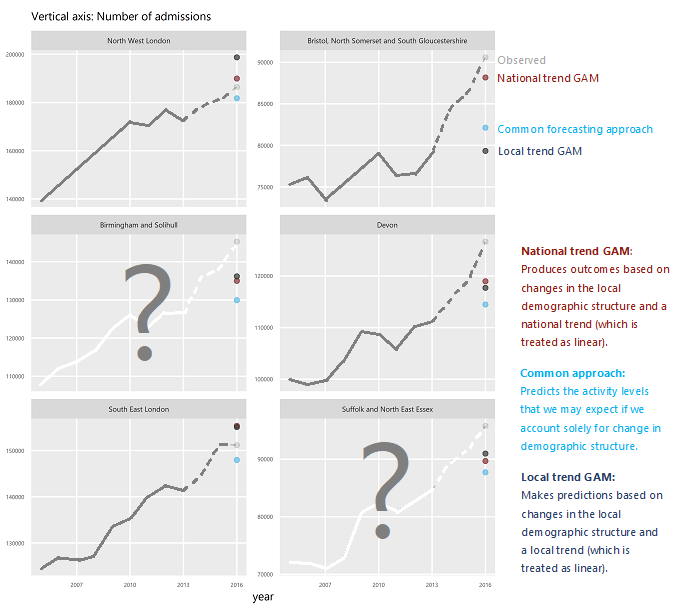

Central to the blended system is the recommendation that commissioners and providers reach agreement on “planned” activity levels (the future activity that might be expected under normal circumstances). The provider’s subsequent performance is measured relative to these levels, and rewards or penalties allocated. It is therefore vital that these levels be fair and credible, and that the methods used to create them be authoritative and transparent. Moreover, these levels must be calibrated to support the objectives of the national healthcare system.

Yet, official documents offer little detail on these crucial planned levels, and no firm guidance on how to produce them. This is problematic since falling back on conventional forecasting methods in this context may lead to the unfair allocation of millions of pounds worth of incentives and a missed opportunity to improve commissioner-provider relations.

This paper has three objectives:

- To illustrate the workings of the blended payment system.

- To demonstrate that inappropriate modelling of “planned” activity levels could divert tens of millions of pounds away from the emergency care system.

- To pinpoint the reasons why conventional forecasting approaches are unsuitable in this context, and to suggest alternatives.

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.