In this long read, Fraser Battye describes our analysis of what has driven the growth in hospital activity. The answer is perhaps surprising.

Press coverage of busy hospitals often comes in the language of natural disasters. ‘Rising tides’ or ‘waves’ of need ‘flood’ wards and corridors across the country.

Explanations for such disasters focus largely on the health of the population. Older, sicker, weaker and less resilient: with the NHS struggling to keep its head above the resulting water.

Health policy is, of course, more subtle in its explanations. But the declining health of the nation is always high on the list of reasons for NHS pressures. 2014’s ‘Five Year Forward View’, for example, argues that:

“…as the ‘stock’ of population health risk gets worse, the ‘flow’ of costly NHS treatments increases as a consequence….Put bluntly, as the nation’s waistline keeps piling on the pounds, we’re piling on billions of pounds in future taxes just to pay for preventable illnesses.”

And this was before the jabs.

More recently, the opening paragraph of Sir Keir Starmer’s foreword to the 10 Year Health Plan points to “a society that is slowly getting sicker”, before the executive summary states that:

“…the NHS now stands at an existential brink. Demographic change and population ageing are set to heap yet more demand on an already stretched health service.”

These accounts are true. Older, less healthy populations contain more need for healthcare. And the state of the nation’s health, with its horrifying inequalities, demands action: in and of itself, and also because of the opportunity to make better use of NHS resources.

These accounts may be true, but they are also incomplete. Demography explains the growth in hospital activity in the way that David Bowie’s success can be understood via his fashion sense: it matters, but it also ignores a more fundamental explanation.

So what does explain the growth in hospital activity?

In 2012, the OECD reviewed 25 models designed to forecast growth in healthcare; they noted that:

“Virtually all models account for demographic shifts in the population and some focus specifically on scenarios about the potential future health status of older people. The models reviewed here, however, point to innovation in health care as the more important driver.”

They cite work suggesting that innovation, and the ever-expanding array of diagnostic and treatment possibilities, accounts for around half the observed growth in expenditure. The OECD then adds that:

“…technological advances and the intensity of their use are among the least well measured and modelled drivers”.

This is flabbergasting. In an area of such high public expenditure; in a service known for its reverence for data and evidence; and in a context of hot fiscal and political debate: how do we know so little?

Why, given the overwhelming role of innovation in increasing activity and cost, is more policy and research attention not invested in this topic? Why is what sometimes goes by the not-at-all-catchy title of ‘non-demographic growth’ not better understood?

The Strategy Unit and colleagues in the New Hospitals Programme have recently made some headway. Analysing several service areas, we examined explanations for recent growth in hospital activity. The full paper is here, but the headlines – along with a ‘test yourself’ style quiz - are below.

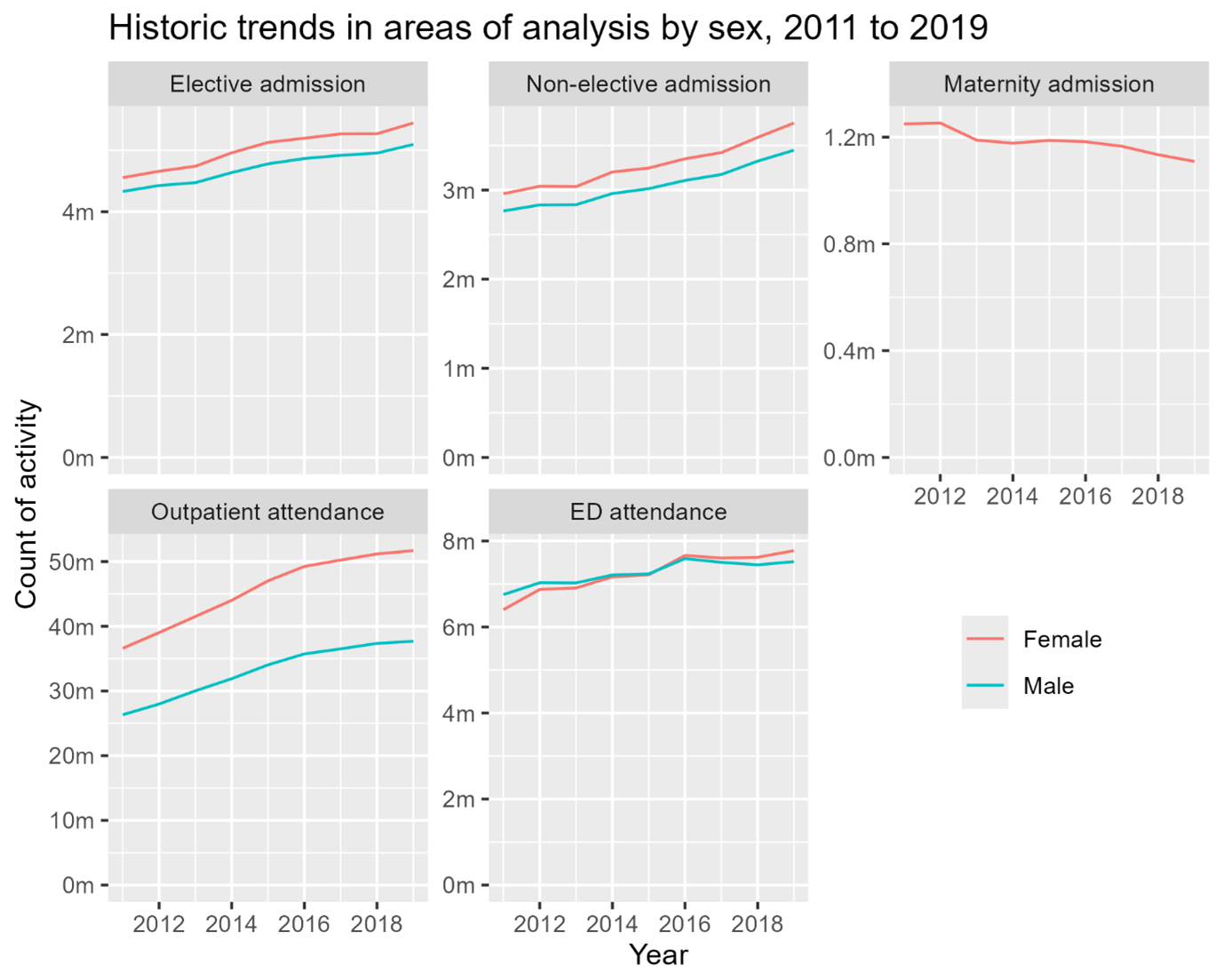

Analysis covered activity between 2011 and 2019 - so missing any effects of the pandemic - and looked at:

- Elective admissions.

- Non-elective admissions.

- Maternity admissions.

- Outpatient attendances.

- Emergency Department (ED) attendances.

Quiz season is over. But maybe rank this list: which areas (a-e) do you expect the most / least significant growth in?

The analysis then examined what explained changes in activity levels, using four factors:

- Population growth – to capture the effects of there being more people who might need care.

- The age and sex of the population – primarily to reflect changes following from an ageing population, as well as changes in demand for services used more by one sex or another.

- Health status – to see how far changes in hospital activity could be explained by levels of morbidity in the population, having taken account of its age-sex structure. (The full paper describes a new measure called ‘health status age’).

- ‘Non-demographic’ growth – residual changes not explained by the demographic factors above. This would include medical advances, innovations in diagnosis and treatment, changes in what patients expect, policy and funding, etc.

Again – and perhaps you’ve now been primed to predict correctly - perhaps ask yourself which factors explain the greatest levels of change in hospital activity…

The table below reveals the results. Please mark your own answers.

| Growth attributable to… | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth per annum | …population size | …age-sex structure | …population health status | …non-demographic changes | |

| Outpatient attendance | 4.51% | 0.61% | 0.46% | -0.02% | 3.41% |

| Non-elective admission | 2.69% | 0.59% | 0.25% | 0.18% | 1.65% |

| Elective admission | 2.29% | 0.88% | 0.69% | -0.03% | 0.73% |

| ED attendance | 1.29% | 0.27% | 0.09% | 0.09% | 0.84% |

| Maternity admission | -0.70% | 0.41% | -0.08% | 0.00% (NA) | -1.02% |

Readers wanting a full and caveated set of results are kindly referred to the paper. But these headlines show that activity increased in all service areas, apart from maternity. Growth was highest in outpatient attendance, which also has by far the highest volume of activity (reflected in the charts below, which show trends over time).

But perhaps it is the explanation for growth that is perhaps most interesting. Firstly, changes in health status, over and above that which can be explained by age, alters very little. And secondly, with the exception of elective admissions, changes in hospital activity are primarily explained by non-demographic factors.

These results are not the final word. They are a useful contribution, yet they remain frustratingly imprecise. Our work on this topic will therefore continue. We are – again with colleagues at the New Hospitals Programme – about to start work to decompose non-demographic growth still further. This will provide separate historical estimates and forecasts for growth arising from: new procedures; changes in medical practice and standards; and changes in patient expectations of the health service.

Non-demographic growth and the shift from hospital to community: a circle that won’t square?

Stepping back, it is possible to see how non-demographic growth (perhaps with a re-brand) might yet move from niche analytical interest to ‘explanation for policy failure on a grand scale’. Certainly, it brings innovation’s frequently overlooked role in resource allocation clearly into view.

In his most recent review of the NHS, Lord Darzi looked at efforts to shift care from hospital to community. He noted that this ambition was both long-standing and unsuccessful. Indeed, his analysis showed resources and activity shifting ‘from community to hospital’, rather than the other way round.

Darzi’s diagnosis for this failure included many factors: financial flows, data and performance management attention, large-scale reorganisations, and so on. But he did not look at non-demographic growth, and the way innovation drives resource allocation. And Strategy Unit analysis for the Health Foundation (described here) suggests that this is a major factor in drawing resources towards hospital-based specialities.

From this angle, we can see what looks like a large and under-appreciated tension at the heart of health policy. The 10 Year Health Plan majors both on innovation and community-based care, but non-demographic growth suggests a trade-off between the two.

If this is right, then we can have high levels of innovation and growth in cutting-edge medicine, or we can have a less hospital-centric NHS. It is hard to see how both can come about - unless very particular policy efforts are made. As a minimum, it would require clarity as to why things would be different this time: how might innovation be guided to reducing costs and shifting care into community settings?

This is a difficult pill to swallow. But perhaps there is a fundamentally encouraging message here too.

Improving population health is a notoriously complex and difficult undertaking. Relative to this, non-demographic growth seems tractable because it follows directly from deliberate policy choices. It can be altered, rather than just responded to; perhaps it is less like a tidal wave and more like a tap.