All medicines are poisons. Everything that cures could kill if administered in the wrong doses, to the wrong people, at the wrong times, in the wrong ways. Paracelsus, a pioneer of toxicology, knew this well:

“What is there that is not poison? All things are poison and nothing is without poison. Solely the dose determines that a thing is not a poison.”

What Paracelsus knew in the 16th Century seems to have been forgotten in modern day policy (and, arguably, politics), where the preference is for clean stories of ‘more good and less bad’. So it was with hesitancy that we, on behalf of the Integrated Care Systems in the Midlands, looked at the balance of harms and benefits associated with increased diagnostic activity.

The arguments in favour of increasing diagnostics are so obvious that they are almost intuitively available. They are summarised in the conclusion of a recent Kings Fund analysis:

“The centrality of diagnostics to the NHS’s ability to deliver patient services cannot be understated…They are fundamental to clinical decision-making. There is huge potential for diagnostics to play an even greater role in driving improved outcomes through transformation and innovation, particularly via the redesign of patient pathways and the introduction of new technology.

Concerted policy focus and investment will be needed…if the major expansion of diagnostic capacity that is needed in the NHS is to be realised.”

This analysis was industry sponsored. Even allowing for that, these claims seem compelling. More accurate, faster, more convenient, personalised information to guide clinical decision making. These are all good things. Who could reasonably object to wanting more of them? Surely – as the Kings Fund argues - more diagnostics are needed?

But, with the possible exceptions of clean water and anaesthetic dentistry, all good things come with downsides. Light casts shade. And nothing is so good that more and more of it leads to better and better results. At some point diminishing returns must set in. And, at some further point still, related harms emerge.

So policy must deal in dose and degree, not black and white. The task is to balance trade-offs such that upsides outweigh the downsides. In the case of diagnostics, the major upsides are reduced uncertainty and therefore better targeting of treatment. But what are the downsides? What trade-offs do policy makers face as they seek to expand diagnostic capacity? And how close are we to diminishing returns: to what extent are gains in knowledge translating into better treatments?

The policy intention in this area has been unambiguously in favour of expansion, and it has been effective in these terms. We found that:

- For those seen in A&E and discharged home, the number of tests per attendance has doubled in the last eight years.

- The number of “key” diagnostic tests requested for elective patients doubled between 2008 and 2020.

- In 2011/12, around 1 in 5 admitted-patient spells involved a “key” diagnostic test. By 2021/22 this had risen to almost 1 in 3.

This growth will have brought benefits. Many of the desired upsides will have been realised, even if some portion of testing is unnecessary (a figure of 10% is reported in the literature); treatments will have been better calibrated and better outcomes will have resulted.

But what of the knock-on consequences? In an interconnected system of services, growth in one area will have effects in another; so our analysis took a systems perspective to examine these effects.

Following the logic that diagnostic activity has to change care (services ordering tests have to wait for and then use the results), we find that growth in diagnostic testing has led to:

-

Longer waits and overcrowding in emergency departments. Here we estimate that around 300,000 patients breached the four-hour target in 2018/19 due to increases in test rates since 2012/13.

-

A longer waiting list (and longer waits) for elective treatment. If the NHS had, for example, maintained the 2012 rate of testing until 2020, then it might have entered the pandemic with a waiting list of 1.5 million instead of 4.4 million.

-

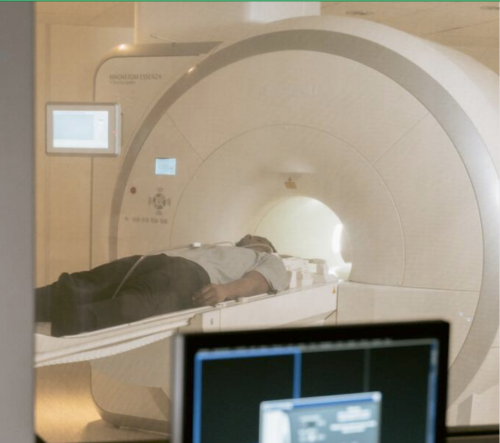

Longer stays in hospital and decreases in bed availability. We estimate that approximately 1,500 hospital beds (of 100,000 total) are occupied today as a result of the growth of just three key tests since 2011/12 (CT scans, MRI scans, and echocardiograms).

The essential argument for diagnostics is clear: information is needed to calibrate treatment; without this information it is difficult to balance the trade of risks and benefits; and if decision makers can’t see these trade-offs then poor outcomes may result.

This is true for decision making in both clinical and policy settings. Our hope therefore is that this analysis provides a diagnostic result for policy makers to use. Showing and scaling some of the downsides of diagnosis is essential to prescribing the right treatment for the whole system.