The resurgence of uncertainty

In 1992, the American political scientist Francis Fukuyama published his book The End of History and the Last Man. In the book, Fukuyama surveyed global trends at the end of the Cold War and concluded that history had ended: that humanity, having experimented with and discarded different arrangements, had now universally and finally settled upon variants of liberal democracy and capitalism.

When he wrote, and for some time beyond, Fukuyama’s thesis had some resonance (at least in the West) but, more recently, history has reasserted itself. What Fukuyama saw as a final destination now seems like a phase; nationalism, protectionism and authoritarianism have re-emerged; reverberations from global economic shocks are altering the terms of the social contract; and technological advance has made control of data into an increasingly valuable commodity.

Dynamics such as these – and the ongoing uncertainties around how they will play out – make it vital that organisational leaders have access to tools for exploring uncertainty. In the NHS, organisations will readily spend large sums of money on procuring projections of how the future is expected to play out: these projections rarely stand the test of time. Perhaps more importantly, they risk creating an addiction in senior managers to the security and certainty that appears to be on offer (perhaps partly because the system to which they are accountable often requires such assurance).

The most dangerous forecasters are those who have just been right because, most probably, they have been right for the wrong reasons and you are tempted to believe them.

Scenario planning is one tool that could be a useful addition to the NHS repertoire, as our recent support for the transformational work being advance in Dudley has shown. The significance of the changes planned – along with the length (10-15 years) of the proposed £5.5bn contract - led the Strategy Unit to propose the use of a scenario methodology as a means of future proofing their multispecialty community provider strategy. To the best of our knowledge, the Dudley health and care system has pioneered such an approach within the National Health Service’s New Care Models programme.

We believe that, while there are some isolated examples of scenario planning in NHS organisations, the scenario method has a much greater potential to help shape a more resilient and agile future for the NHS and its partners (not least at local level), and to assist current and emerging system leaders in seeing beyond the pressing challenges of today and the established ways of framing those challenges. It doesn’t offer certainty but it can generate understanding, shared learning, system resilience and organisational agility.

The scenario perspective

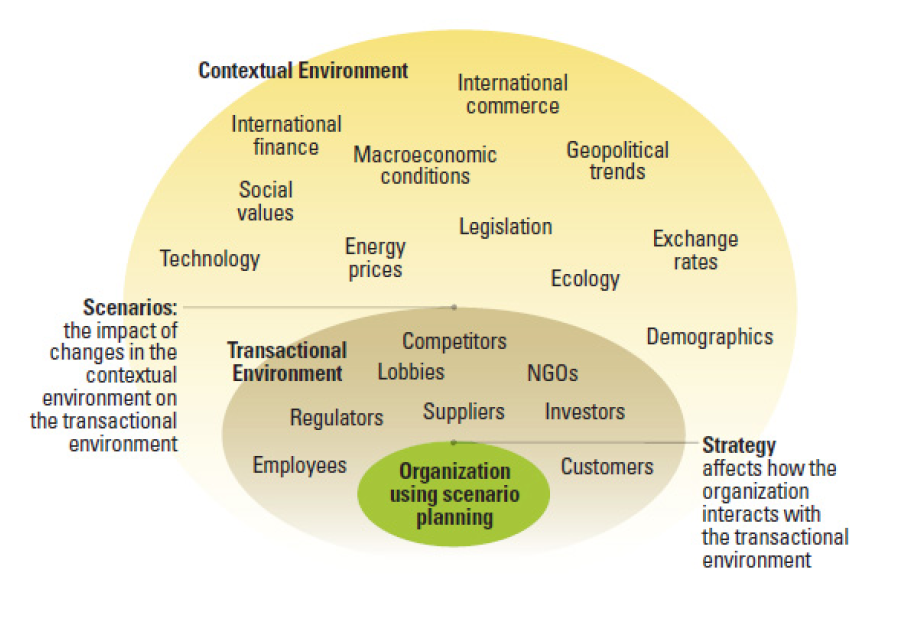

Scenarios are plausible descriptions of alternative futures that enable organisations to plan better for the present. Typically, a small number of contrasting scenario narratives are developed that address the contextual environment in which an organisation operates (see figure below[1])

There are multiple possible approaches to scenario planning, and this makes it a very flexible tool that can readily be tailored to the context of each organisation that uses it, whether at the outset of building a new strategy or as a means of ‘wind-tunnelling’ a planned strategy (as in the Dudley case). The method[2] seeks to assist organisations to make strategic decisions in uncertain, novel, turbulent or ambiguous circumstances by creating and reflecting on a diverse set of plausible narratives about how the organisation’s wider contextual environment might evolve over a given period. It has an intensely practical focus and enables participants to view – and, where appropriate, to revise – their plans from perspectives that they are unlikely to have considered otherwise. Being right is not the goal; being able to learn is.

Eric Hoffer observed, "In times of change learners inherit the earth; while the learned find themselves beautifully equipped to deal with a world that no longer exists." They anticipate rather than react to change. They become essential facilitators within their altered environment. They are effective advocates for principled behavior and ethical practices.

The Shell experience

The growth in the use of scenario planning since the 1970s has been driven, in large part, through its deployment by Shell. It was scenario work that enabled the company to better ride the turbulence of 1970s oil price crises because it had conceived that historically stable prices could change significantly and it had considered how it should act if they did. The method’s value lies in reframing established perspectives, patterns of thought and perhaps unquestioned assumptions. The shipping division in Shell isolated itself from this learning and paid the price in multi-year losses having continued to build vessels that were no longer required.

Subsequently, the scenario sets that continued to be developed and refined became key to major strategic decisions. Business case approval depended on demonstrable resilience against each scenario. By contrast, major NHS investment decisions – such as for the development of a £300-500m hospital – will generally only consider one (preferred) scenario with income and expenditure projected for 60 years.

More recently scenario analysis has led Shell to conclude that demand for oil is likely to peak sooner than expected. As a result, it sold $7.25bn of its Canadian oil-sands assets and reinvested the proceeds in developments that are expected to offer more resilient returns.[3]

Is it for you?

Pierre Wack was a key figure in the use of scenario planning within Shell and spread its influence more widely. He observed that

You only need planning when the speed of change of the business environment is faster than your own speed of reaction.[4]

Scenario planning will not benefit all organisations in all circumstances but it can be an invaluable addition to the manager’s repertoire when there is a danger of being caught unawares.

A recent McKinsey study of more than 1,000 major business investments showed that when organizations worked at reducing the effect of bias in their decision-making processes, they achieved returns up to seven percentage points higher.

If you are an NHS, other public sector or third sector organisation and you sense that the scenario approach may have something to add to the big calls you are about to make or to your organisation’s thinking about its future focus then we’d be very pleased to hear from you.

Scenario work can take many forms, ranging from:

-

An extended exploration over a number of months, drawing more or less heavily on qualitative and quantitative data, and on interviews with local stakeholders and national/international experts in relevant fields; to

-

A single workshop perhaps using pre-existing scenarios that have an applicability to what you are considering but which still enable valuable stakeholder interaction of a kind that might not otherwise be accessed.

We can’t ensure you’ll be right but we can help you to be more alert and better prepared, and to generate a culture of collaborative learning that can enrich all aspects of what you do.

[1] Using Scenario Planning to Reshape Strategy, MIT Sloan Management Review, Summer 2017 (Ramirez et al, 2017). https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/using-scenario-planning-to-reshape-strategy/

[2] We largely use the Oxford Scenario Planning Approach due to the extent of experience and evidence associated with it – see https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/using-scenario-planning-to-reshape-strategy/