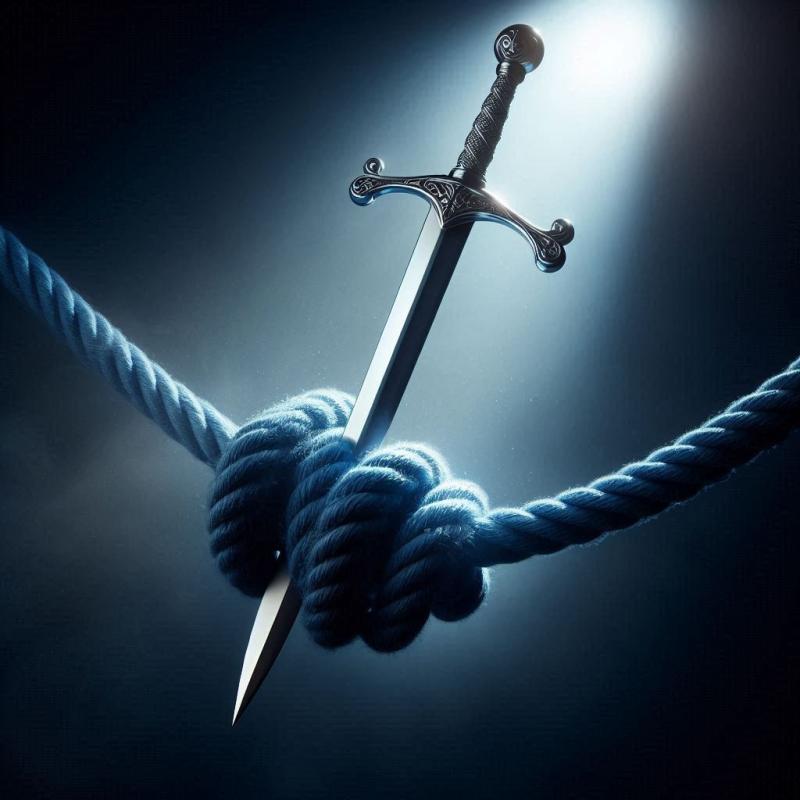

In Part 1 of this blog our Head of Policy, Fraser Battye, described English health policy as a Gordian knot. In Part 2, he looks at the weapons available to cut it.

The Gordian knot was, according to Greek myth, so tightly bound and so complex that it could not be untied. Many tried and failed.

But Alexander the Great resolved the problem without detailed fiddling. He employed a single and decisive blow from a sharp sword: slicing straight through the problem.

Are there political and policy equivalents that might help English health policy’s knot?

Maybe. But none are simple - and some are hidden behind other temptations. Here is a very partial survey of available weapons.

Structures, contracts and incentives: a broad sword (wield with care)

‘Reform’ has often been conflated with - and, in practice, cashed out as - ‘reorganisation’. It is to be hoped that Streeting has seen that this invariably ends in expensive disappointment. Our analysis of 'Transforming Community Services' showed as much: despite apparently strong competing arguments about different ways to organise community services, and the investment of significant managerial efforts, this reorganisation made no perceptible difference to the key outcome of unplanned admissions for older people.

And yet, current arrangements contain strong pulls away from more community-based care. Payment by Results, Foundation Trusts and a sharper internal market were used by the previous Labour government to remedy the problem of waiting lists. They worked. Allied to significant increase in resources, these actions addressed the problem.

But the cure lingered, before going on to create problems of its own. The result today is a powerful acute sector, underpowered local commissioning, and largely ignored community services.

How will care be rebalanced if this remains unchanged? The presence of Paul Corrigan and Alan Milburn – architects of Labour’s previous reforms – is interesting here. Will they now use similar policy instruments to shift the locus of care away from hospitals? Will they create contractual incentives for getting someone out of hospital, or for maintaining someone’s care at home? And how will this shift of resources be balanced with the pressing need to reduce waiting lists?

Experiences at the end of life would make an excellent bell weather here. Will services be reshaped to give people a good death? Analysis we did for Macmillan suggested that increased contact from community services was key to this. The way we care for the dying is an important measure of the health and humanity of our NHS. And care at the end of life can be resource intensive. If contracting is to help make better use of resources and improve care, then this would be an excellent indicator.

Digital technology: efficient laser or expensive mirage?

Streeting’s third shift – from analogue to digital – will have all the appearance of a sharp and shiny blade (or perhaps a laser) to sever the knot. The core promise of digital technology is efficiency and productivity. And getting more for less means making fewer unpopular choices.

And yet experience suggests that it (IT) will cost more, take longer, and deliver less than is promised. Darzi’s suggestion is that the NHS ‘tilt towards technology’. This is a useful phrase: ‘tilt’ is used by poker players to describe emotionally clouded, desperate decision making: something we would do well to avoid.

Better tech is clearly part of the mix. It always has been. But hopes should be calibrated against previous experience, rather than breathless excitement about possible futures. And our (forthcoming) analysis of the downsides of digital technology should help guide choices here.

Regulating for better public health: trusty but rusty

Public health measures are a more promising blade, even if it has been left in the sheath recently. At the policy level, the calculation hinges upon these measures being vastly more cost-effective than treatment. This can also be attractive if regulation doesn’t incur significant upfront costs (at least for government). It also won’t be difficult to spot preventative opportunities: and some – notably those that also address worklessness – may also help the UK’s productivity problem.

The standard political calculation for public health measures is about what the public will wear, given apparent desires for personal freedom. This assumption is well worth exploring (it dissolved during lockdown). Knowing that we have become less healthy as a nation, what appetite is there for a far greater emphasis on prevention via regulation? Are there political moves that clarify and alter the basic deal between citizen and state? Could this be clarified through detailed and sophisticated public engagement?

Obesity will provide a useful litmus test here. We will have made the ‘shift from treatment to prevention’ if we avoid injecting and operating our way expensively out of a socially created problem.

Social care: cutting edge or third rail?

It is easy to understand political allergies to social care. It remains to be seen how far Labour’s ambitions for a National Care Service come to pass in practice (they were muted in the manifesto). Policy consensus, public opinion and political will have yet to coincide. Will a Royal Commission help them to?

Something will happen, even if it is not politically driven. Baby boomers will move slowly through and out of the social care ‘system’; some of them will be financially ruined by it; effects will wash through our politics; the social care market will change. Social care could play a central role in a more localised, more community-based model of care. Will political and policy reforms make this a durable reality?

Cutting out poor decision making: an overlooked weapon?

Everything above places faith in policy and politics. There is a more human scale change, that would be felt instantly at the frontline of care, in people’s lives and – over time – in budgets.

In recent years, the Strategy Unit has done a great deal of work to help decision makers use our analysis. Our focus on the quality of strategic decision making has an excellent, evidence based and deeply promising parallel.

Al Mulley, clinician, academic (and friend of the Unit) has long promoted ways of improving clinical decision quality in primary care. His essential point – elaborated in a recent podcast and Scotland’s 'Realistic Medicine' movement – is that better decision quality at this point in care pathways leads to more appropriate (and typically more conservative) uses of care.

We could save resources and regret. Might many small cuts sever the knot?

Sharpening the sword

This blog provides a very limited survey. Even this has shown the requirement for political boldness allied to imaginative policy. The current bind will prove difficult to release.

We wouldn’t be the Strategy Unit if we didn’t end by pointing to the need for the skilful use of research and analysis. Every means of cutting English health policy’s knot will be sharpened by high-quality evidence.

By its very form – data everywhere, 445 footnotes, 331 page technical annex – Ara Darzi’s review makes this exact case. Evidence is foundational to his whole report. And, from this vantage point, he concludes:

‘The NHS is now an open book. The issues are laid bare for all to see. And from this shared starting point, I look forward to our collective endeavour to turn it around for the people of this country, and to secure its future for generations to come.’

The Strategy Unit looks forward to playing its part.