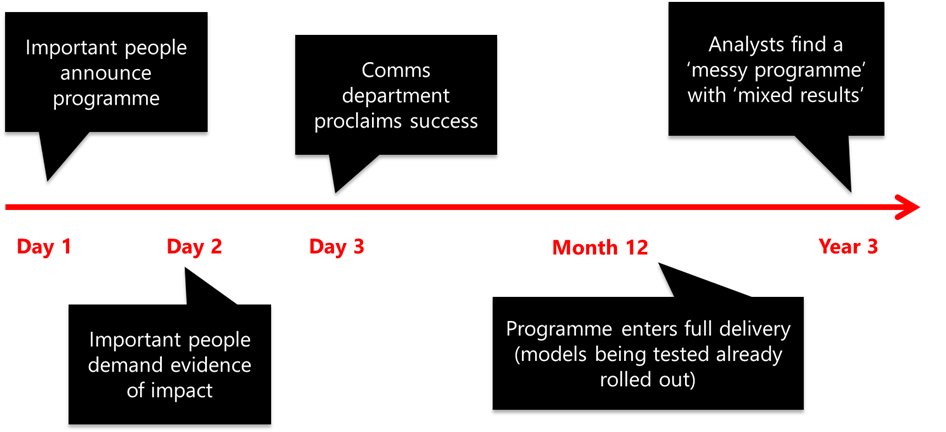

The diagram below shows me at my most cynical. It is from a (light-hearted…) session that I ran many, many moons ago, where I was trying to describe the environment for evaluation that can be created by high-profile NHS programmes.

My main point was about the clash of cultures and incentives between what I have called ‘important people’ and analysts. Crudely, my suggestion was that people leading change are incentivised – largely because of their proximity to the political sun – to proclaim success ahead of anything like empirical evidence. Not because they are ‘bad people’, but because of the sheer weight of pressure on them to do so.

I was reminded of this slide – and the final box especially – when reading the paper below. Produced by (the wonderful) Shiona Aldridge, it began life as a quick internal Strategy Unit working paper; but she saw the value of sharing it more widely.

The purpose of the paper was to feed a model looking at the expected impacts of shifting care from hospital to community. More specifically: might we expect a reduction in unplanned hospital activity, and – if so – at what scale?

Analysts find a ‘messy programme’ with ‘mixed results’ would have been a decent title for the paper. Shiona patiently sifts through the literature, detailing several factors that have held programmes back, such as:

- Flawed programme design and unrealistic assumptions.

- Lack of attention to context.

- Unrealistic expectations and narrow objectives (including using unplanned hospital activity as the central measure).

- Challenges with implementation.

- Unintended consequences.

- Difficulties measuring impact.

These topics will be familiar to anyone with a history in and around integrated care. And, in addition to its reassuring if depressing familiarity, the paper is worth reading for two further reasons.

Firstly, it will be useful to anyone trying to make evidence-based assessments of one likely impact of shifting care from hospital to community. Having been in situations where an evidence-free ‘assume 10%’ has been used, this will be helpful in and of itself.

Secondly, it may prompt broader thoughts about policy and programme design. Indeed, it may prompt questions about the reasons for evaluation and the foundational value of evaluative evidence.

In approaching these broader questions, we should retain modest hopes. The NHS will forever, and probably rightly, be tossed around in political waters. Its senior representatives will always therefore face incentives to seek neat ‘good practice case studies’ and sunny stories of success. ‘Messy programme with mixed results’ will never cut it in a politically charged environment. Perhaps the space for evaluation will always be heavily curtailed?

But the paper really made me think about missed opportunities over time. On and off, health policy has emphasised the shift ‘from hospital to community’ for around five decades. And there are reasons to think it will be doing so for decades to come.

The problem is highly durable. Given this, every programme could be approached as an opportunity to learn rather than fix. Success would be ‘incremental progress’, plus ‘insights to use next time’.

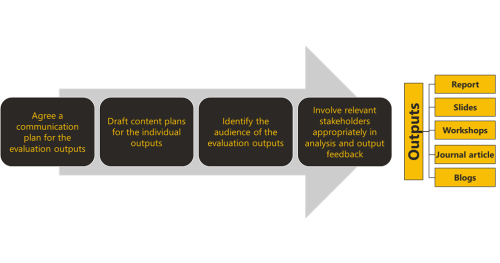

The main change required would be in programme design. And the aim here would be to make them easier to evaluate. Programmes could – even just through the addition of a theory of change – become less inherently ‘messy’, with results that are easier to interpret. Lessons could cumulate over time, allowing every programme to draw lessons from its predecessors.

And, by adopting a slightly more evaluation-friendly environment, there would also be fewer opportunities for cynics to produce droll diagrams…