Hospices are fundamental to end of life care, and the broader shift ‘from hospital to community’. But, relying on charitable income, they are in financial trouble. In an article first published in the Integrated Care Journal, Fraser Battye, asks ‘what is to be done’?

Even distant followers of health policy will, by now, have heard of the plan to ‘shift care from hospital to community’. Slightly more careful observers will know about the ‘Neighbourhood Health Service’. And a particular variety of obsessive will be familiar with ‘strategic commissioning’.

In each case, we might ask: how would we know if these initiatives were successful?

End of life care suggests itself as a general test. Each of these initiatives points towards more community-centric, joined-up, locally-based care. If this doesn’t mean better support for the dying and bereaved, then what does it mean?

And, in some ways, starting conditions are as favourable as they will ever be.

For a start, the problem is well described. There are some excellent analyses of the current state of care at the end of life. Strategy Unit analysis for Macmillan, for example, shows the demographic, socio-economic and service-related conditions that tend towards better or worse outcomes. And analysis for Marie Curie, by the Nuffield Trust and (our sister team) the Health Economics Unit, shows how resource use could be changed.

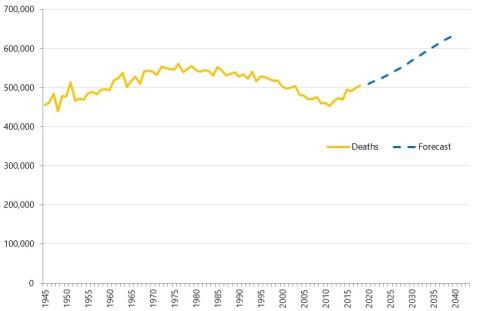

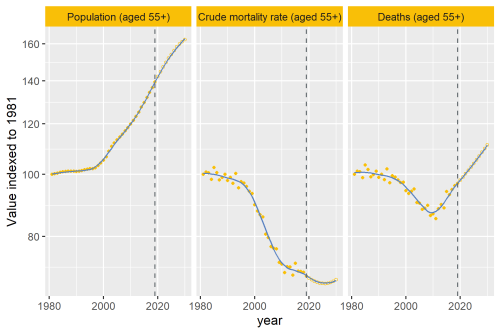

The problem is also slow moving. Driven predominantly by demographic change, it is possible to see – and even animate - a coming wave of death. This is not a problem of the unforeseeable and rapidly evolving variety: it is moving steadily, and predictably, into view.

Solutions are also largely agreed upon. The Lancet Commission on the Value of Death – summarised in this really quite beautiful video – sets out what it calls a ‘Realistic Utopia’. It is a vision that resonates with moves in the NHS to make more careful use of medical intervention at the end of life. A holistic understanding of people’s needs in the foreground; medicine playing a supporting role.

Hospices are central to this. From its roots in the late 1960s, this largely charitable movement has grown and evolved. Today, hospices provide specialist care that addresses the physical, social, spiritual and psychological needs of the dying and their loved ones. This care extends out of hospices and into community settings; hospices also engage in research, education and multi-disciplinary clinical work.

This seems like a rare confluence of problems, solutions and policy drives. Community based care at end of life alleviates suffering for the dying and their families; it reduces pressure on hospitals and makes better use of scarce resources; there is broad consensus on the way forward; and there are organisations designed to do it. If we can’t make this work, then it’s hard to see how more ambitious elements of the care shift will ever take hold.

But all is not well. What looks straightforward at first glance is revealed to be devilishly complex upon a closer look. Money, as ever, is part of the story.

The hospice sector has real financial problems

Last month, the National Audit Office (NAO) reported on the financial sustainability of England’s adult hospice sector. The headline? Demand is increasing while supply is tightening.

The NAO notes that:

- There were around 544,000 deaths in England in 2023; this is projected to rise to 658,000 by 2044.

- In 2024, for deaths in England: 5% died in a hospice inpatient unit; 28% died at home and 21% in a care home; 42% were in hospital.

- Most people would prefer to die at home or in a hospice. Current trends are in line with this wish: the proportion of hospital-based deaths has been decreasing.

- In very broad terms, around two-thirds of the funding for hospices comes from ‘charitable sources’ (shops, legacies, donations, fund raising, etc). One-third comes from the NHS. A few hospices rely almost entirely on state funding; others receive very little.

- The sector’s income is falling. Around two-thirds of independent adult hospices recorded a deficit in 2023/24. Services are being cut to address this shortfall.

- Around a third of expenditure in the sector goes on income generation. The rate of return is decreasing. In 2023/24, every £1 spent on fund-raising returned £1.96; the historic rate has always been above £2.

- Specific initiatives have changed government and NHS involvement in hospices’ income. This has included one-off injections of capital funding, pandemic-related support, and – perhaps most significantly - The 2022 Health and Care Act requirement for Integrated Care Boards (ICBs) to commission palliative care services.

- ICBs currently discharge this duty through a mix of grant funding and contracting. Where grants are used, there is a lack of transparency and data. Where contracts are used, there are no national tariffs for pricing.

This is not sustainable. And, although the NAO doesn’t say it, every decline in care provided by hospices adds pressure to already overstretched and overcrowded hospitals.

The current situation is not viable. Where might change come from?

One way of approaching this question is to look at the role of the state. The usual way of securing services deemed important to public wellbeing is through taxation and state funding. This boundary is always contested and will never be clear (see social care); but it is legitimate to ask whether hospice services should be more ‘mainstream’ than they are.

This case is being made by the sector. Giving evidence to the Health & Social Care Committee (July 2023), Hospice UK’s Jonathan Ellis said:

“Hospices…rely on charity donations for the vast majority of the care that they provide - fun runs, charity fundraising and bake sales to fund what, in any reasonable perspective, is a core healthcare service.”

There are more and less thoroughgoing ways that hospices could be made a core NHS service. Most radically, if the state wanted to take full responsibility for the current funding shortfall, the NAO report suggests that annual funding of around £0.5 billion would be needed. This would cover the level of charitable income, less the money spent on fund-raising. Doing so would more than double current NHS expenditure on hospices.

It is unlikely that government will want to go this far. Nonetheless, there is a widely accepted case that the funding mix must change. Pressure will continue to build. The NAO report suggests that, without action, things will get worse.

So where might action come from? I see two main sources.

The first is politics – and current debates on assisted dying. The NAO pointed to this live rail, concluding that:

“With the number of people in England who die each year increasing, and the key positioning of high-quality palliative and end-of-life care in the assisted dying debate, the sustainability of the independent adult hospice sector is of national importance.”

Sam Friedman, in his recent wide-ranging ‘Comment is Freed’ post furthers this argument. Joining two contentious dots, he says:

“[Assisted dying] will probably be publicly funded which raises questions given other forms of end of life care are not … this could act as an incentive for assisted dying.”

This would be unpalatable for most of us – including Wes Streeting, who, while speaking about his opposition to assisted dying, said that:

“I worry about palliative care, end‑of‑life care, not being good enough to give people a real choice…I really worry about those people who think they’ve almost got a duty to die to relieve the burden on their loved ones.”

Any such ‘duty’ would be unevenly distributed. There is evidence of unequal experiences of palliative care by demographic group (skewed in favour of the wealthy). And the NAO reports incredible geographic variance in inpatient hospice provision. They show that, in 2023/24, one ICB area had one bed per 2,900 population aged 65+, when another had one bed per 54,300. For an NHS sensitive to accusations of a ‘postcode lottery’, this would presumably be intolerable.

The question of who pays for assisted dying may ultimately therefore wash back into wider discussions of hospice funding. This could be a far-reaching, if unintended, consequence.

A second, and related, potential source of change comes from policy. In response to a question in parliament, Stephen Kinnock MP summarised the broad direction of travel:

“The Government is determined to shift more healthcare out of hospitals and into the community, to ensure patients and their families receive personalised care in the most appropriate setting, and palliative and end of life care services, including hospices, will have a big role to play in that shift.”

Key developments here include:

1: Strategic commissioning

The recent NHS England Strategic Commissioning Framework gives ICB’s a clear (if thorny) task: allocating scarce resources to improve the health of the populations they serve.

Given the high proportion of expenditure involved, end of life and palliative care is likely to be a priority. The analysis for Marie Curie referenced above showed that, in the UK, expenditure on healthcare for people in the final year of life is around £12 billion a year. 81% of this is spent on hospital care, and only 11% on primary and community care (including charitable hospices).

Commissioning ‘strategically’ means taking a broader view over time (accounting for looming, as well as immediate, problems) and systems of care. In doing so, ICBs will be aided by Strategy Unit our tools showing the effects of long-term demographic change, and our work to scale potentially mitigable hospital activity - including at the end of life.

Commissioning strategically will also involve developing new contractual forms. Here, ICBs will need to balance competing interests:

- On one hand, public need will be such that some level of specialist, hospice-led provision should be secured through public funding.

- On the other, NHS funding should not displace charitable contributions – and hospices will doubtless worry that the bureaucratic strings attached to NHS funding will constrict their social mission.

Navigating this, ICBs should be well-placed to negotiate the local detail of this balancing act. Perhaps through specifying levels of charitable income that should be maintained; perhaps through clarity about what the NHS will and won’t fund (nursing and medical care, yes; complementary therapies, no); perhaps through setting and measuring outcomes (such as reduced suffering, and a ‘good death’) that matter to people and families.

As a related aside, innovative ‘social financing’ arrangements have arisen in this area. These arrangements typically need additional, and sometimes sophisticated, analytical underpinnings. They could therefore significantly improve knowledge of what works – and will doubtless support some effective practice. But there are reasons for caution too: such arrangements have failed expensively in the past - and good strategic commissioning should not require elaborate financial mechanisms to perform the basic task of (re)allocating resources. There is risk of distraction alongside innovation.

2: The ‘Neighbourhood Health Service’

Neighbourhood health is becoming the mainstay of the shift from hospital to community. The National Neighbourhood Implementation Programme, which the Strategy Unit is happily supporting, has not started with the ‘end of life cohort’ - but it is encouraging and catalysing a model of care that lends itself directly to this.

Local integrated teams - drawing from the voluntary sector, multiple NHS services, social care, and other public services – all seeking a more ‘Do With’ relationship with local citizens. This is entirely in line with the requirements of high-quality end of life care. Hospices perform a vital, specialist, role; harnessing and guiding the contribution made by other community-based services is fundamental.

It would therefore be surprising if forthcoming national guidance on neighbourhoods didn’t feature a specific emphasis on end of life and the role of local hospice care.

The only test that matters: when policy becomes embodied

Health policy necessarily deals in concepts and abstractions. Its basic currency is ideas, and its stock in trade is the narrative. So it is often difficult to imagine what things like ‘neighbourhood health’ or ‘strategic commissioning’ or ‘shift from hospital to community’ might mean in practice.

But, at some point, the abstractions of policy become embodied and experienced. The ultimate test of health policy is the extent to which it reduces actual, felt human suffering. End of life is a deep source of real suffering. It is also growing. The sustainability of the hospice sector is therefore a critical issue for people, policy and the NHS.