Within months of the COVID-19 pandemic, international evidence on the disproportionate impact of COVID by race and ethnicity began to emerge in countries that collect ethnicity data (the UK, USA, Canada, Norway and Brazil. Each provided more evidence that people living in a country where they were classified as minority ethnic, had a higher risk of contracting COVID-19 infection with more severe outcomes when infected. As a response to this emerging data, the Strategy Unit undertook a small exploratory qualitative study between June and August 2020. We publish these stories, two years into the pandemic as a historical reflection.

We recruited via our own personal and professional networks to reach people who are often considered ‘hard to reach’. We conducted 11 in-depth, semi-structured interviews with people who self-identified as minority ethnic and who had experienced symptomatic COVID-19 illness. The purpose of this study was to record individual experiences of: becoming infected with COVID-19; the impact on their households; and, the management of symptoms including how they accessed and used health and care services.

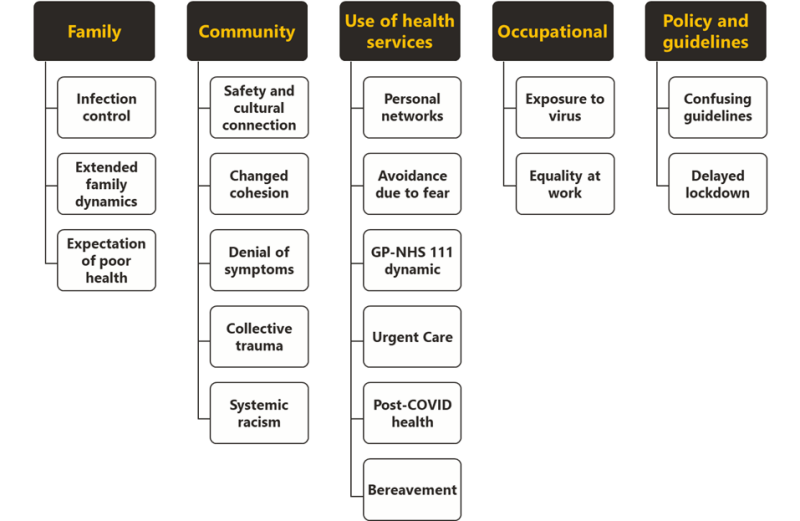

Thematic analysis of the qualitative interview data identified five key themes as shown in the figure above. We previously presented these findings at the Strategy Unit’s 2020 Insight festival.

We are now publishing a summary of each of these interviews as narrative stories, that is first person accounts under the headings of:

- My life before COVID

- My experience of COVID

- My life after (first infection with) COVID

- Why my COVID experience matters

Whilst acknowledging the many overlapping experiences, we have grouped these 11 stories[1] according to three main categories. We have also provided a summary of each of the three categories. The interpretations are situated in the lived experiences of the qualitative team who undertook this piece of work. We were motivated to challenge the overly simplified narrative of linking the poorer pandemic experiences of minority ethnic people with low socioeconomic status, cultural practices and front-line roles. The accounts collected in these interviews reveal both the counter-arguments and the nuances within these narratives.

[1] all names have been changed but where possible matched for ethnicity and religion.

The experience of those we interviewed poses questions around what constitutes a family? And what is a household? For those of us who are of South Asian descent, we understand that the family and household is not limited to those who live in the same dwelling. Rather, family constitutes the multigenerational people that interact on a regular basis: that pop into one another’s homes without warning and invitation; that congregate at the eldest family member’s home on weekends; and where family-decision making can be hierarchical (and patriarchal) and impacts those living outside of the main household.

These accounts illustrate the wide-ranging and complicated family and cultural dynamics which needed to be navigated as people made sense of the pandemic. Where interactions were curtailed, there was much by the way of family tensions: there were not always agreement and support on how to follow lockdown rules, how to keep vulnerable family members safe, or how to isolate when symptomatic.

“There’s also been a lot of tension on the extended family WhatsApp group around the relaxing of guidelines, questioning “what about parents and family rights in all this”. My sisters are very much supportive, but a couple of my brothers have not been. Sometimes there’s a bit of teasing by them to say “you’re very official and legal - we can’t go and see you”. We’ve even been called the COVID police!”

When family members did fall sick with COVID-19, people we spoke to managed symptoms at home as far as possible. Advice from NHS 111 and GP was generally felt to be insufficient and the fear of loved ones suffering alone led to people delaying access to emergency health services. Tragedies such as Dawood’s were further compounded by experiencing bereavement in the absence of community and social expressions of grieving – these are likely to create long lasting community trauma.

“As an Asian family, you don’t let your parents go to the hospital on their own, especially when English isn’t their first language, but we had no choice”

Within this background, the narrative for linking deprivation with minority ethnic groups was fiercely contested by the people we spoke to. This challenge was for both homogenising all people of colour and ignoring personal freedoms in deciding where to live. Many described that they chose to live in areas that were considered deprived because it afforded them the means to access community services or to feel safe from racism.

“Another issue is that we are lumped together with all the other ethnicities. The government shouldn’t just assume that ethnic minorities don’t follow the rules. I’m educated, I have a degree, I have a job, I’m well paid, so is my partner, we live in a three-bedroom house, we own it - even people like me were dying, so it wasn’t that ‘we all live in overcrowded houses’, because we don’t.”

Of the 11 people we interviewed, five were NHS professionals. Whilst we didn’t intend to oversample towards people working in the health services, it comes as no surprise given the ethnic diversity within the NHS workforce. These five NHS staff were each unique in their: roles within the NHS (commissioning, consultant surgeon, non-clinical primary care, community admin, and nurse), ethnicity (Black, Middle Eastern, Indian, Pakistani) and their place of residence (Merseyside, West Midlands, London).

All five of the NHS staff we spoke to expressed strong views on the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on minority ethnic people. They perceived that the higher severity of disease and poorer outcomes to have been avoidable, had prior knowledge of prejudices and health inequalities been acted on.

“I am certain that structural racism, sexism and violence are behind many of the inequalities we've seen as a result of COVID. Not to say that COVID caused them, but COVID highlighted them in a way that could not be denied. It’s infuriating because this is not new knowledge.”

The accounts of these health care professionals showed the occupational risks that NHS staff were exposed to, whether through direct patient care or from office-based working. They also indicated the contrasting treatment of ethnically diverse people who are off sick.

“Anybody else that goes off sick doesn’t have [queries around their sickness absence] - when remarks like those are made, you know that’s purely because we’re Asian”

NHS staff were also frustrated by poor representation of people like them at senior levels of NHS organisations. They linked this to the disconnect between decision makers and communities that had led to inertia in tackling health inequalities with appropriate action.

However, working within the NHS did provide advantages, NHS staff were able to use their professional knowledge and networks to access new information, care or support for themselves or their loved ones.

“Because I work in the health service, I know a Director at one of the Hospitals, so I contacted him and I said I’m a bit concerned for my son, I just need some advice. And he was kind enough to give me their top respiratory consultant. He said look don’t worry, the cough can last a long time. We’re not seeing the cases in A&E that you might think with COVID for children.”

The people we spoke to described the confusion they experienced in making sense of national guidance and the lack of visible action around public safety during the first phases of the pandemic. There was a consensus that the UK lockdown was mandated too late and was insufficient. For example, the perspectives were that borders could’ve been closed earlier, and rules could have been enforced better to capitalise on lockdown and save lives.

“I do feel that if things had locked down a bit sooner then not so many people would have passed away. We picked up the basic information that they told us; to isolate. But when they said one day we’re doing this, one day it’s this bubble, and all that mess-up of information, we ignored it. It actually gives you a headache that they just don’t know what they’re talking about themselves.”

There were requests for more timely, consistent and locally tailored communication of the rules and the need for local agencies especially local government to play a more prominent role within this.

Over-reliance on national government briefings via news channels became problematic because it was either not a usual source of information for many or it became less credible over time. For example when different social distancing rules for different communities became apparent – such as when garden visits were not allowed in the summer of 2020 but socialising at pubs was permitted.

In the absence of clear, accessible and geographically relevant information, the view of the people we spoke to was that their communities could not be fully aware of the guidelines or understand the need to adhere them.

There is alot of things we didn’t know that we were supposed to do. The information about lockdown was not available in the way that it needed to be. Some people follow it very strictly, but some people are not putting the masks on."

Previous Strategy Unit analysis of emergency department use during the first lockdown showed marked differences by ethnicity. These qualitative accounts of minority ethnic British people navigating the first phase of the pandemic for why this was observed. They also provide more nuance to the over-generalised narratives of how ethnically diverse people and communities live and behave.

Two years on, with the emergence of further differences in vaccination rates by ethnicity and faith (see Strategy Unit’s work on increasing vaccine uptake) these stories reiterate that the time to address long-standing issues of prejudice and trust between people and public institutions is now.

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.