Good mental health during early years and childhood has a great bearing on health throughout life. By contrast, poor mental health can cast a long shadow. Consequences may include depression, self-harm, and poor physical health.

Services recognise this. They aim to provide access to support in a timely and suitable way. A national target has been set, namely that 35% of children and young people with diagnosable needs should be able to access the necessary services.

But there is some way to go. There has been an increasing focus on young people’s mental health, which appears to be poor relative to comparable nations and the recent past.

So, to gain a clearer sense of need, and patterns of access to services, the Strategy Unit has undertaken specific analysis for the 11 Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) in the Midlands.

This is another significant analytical project for the Midlands Decision Support Network. The ICS have further evidence to understand and address the problems in their area.

Our findings

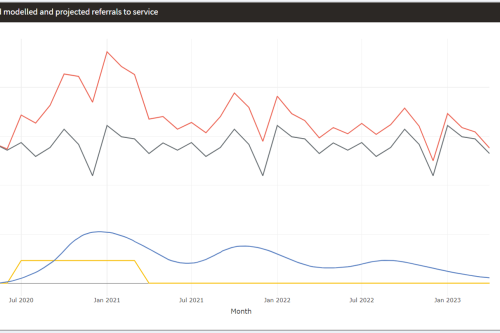

1. Services are struggling to keep pace with existing demand

In the Midlands there are an estimated 350,000 children and young people with a range of mental health needs. At present, only 43,000 of these are receiving some kind of specialist support. Identifying the children and young people who most need support is difficult, with health and care professionals finding it increasingly challenging to reach those concerned. When they do, there is simply not enough support available. For example, our research found that only 2% of the estimated 160,000 children and young people in the Midlands with eating disorders are finding their way to specialist support.

2. There is wide variation in access to services in the region

Even the better-performing areas are only able to provide the necessary support to 30% of those who need it. Children and young people who are Black / socially deprived / aged 18 to 24 / have learning disabilities or autism, tend to struggle more with accessing appropriate support. Health and care professionals suspect that services are not being provided equitably, but current data doesn’t provide clear enough evidence of this.

3. Access targets are a necessary focus, but there needs to be more meaningful analysis on who is, and who should be, using existing services

ICSs need to measure what they are proposing to change. Without the correct data and subsequent analysis, this will prove almost impossible.

4. Routes into and through services need to be clearer

Those that need support often don’t know how to access it. Health and care professionals acknowledge that those better able to navigate the complex services, for example through parental advocacy, tend to have an advantage in accessing support.

5. Children and young people should be involved in improving services

There is limited involvement of young people in improving services. Mental health and care professionals also want this to happen more.

Conclusions

There is no single or quick fix to the problems highlighted in the research. Evidence suggests that the pandemic will have placed an even greater strain on already stretched services. Children and young people, as well as professionals, deserve these services to be given far greater priority, as well as improved resources.

Especially at a time of stretched resources, ‘fixes’ on this scale are not straightforward. This is a long-term, cross-societal challenge: how much do we value young people’s mental health? This question is well outside the scope of our work.

So we have focused our recommendations on more achievable improvements that are within current services’ control. They are to:

Collect better data and use it

Services could improve data collection around aspects of inequity and access. Greater precision is needed. Datasets in primary care, education, social care, criminal justice, and specialist services could all be linked. All data should be disaggregated by gender and ethnicity. Services could consider an investment in analysis and learning from the data, as well as needs assessments.

Measure, monitor and maintain

All new initiatives and interventions should be robustly evaluated, for equity as well as efficacy. It is essential that we all learn what works in what circumstances and that it is shared systematically. Establishing a serious learning system will inform the development and adaptation of promising service improvements; it will also provide evidence to stop any services that are not working and allow resources to be redirected.

Co-design and co-produce

Children and young people deserve to be meaningfully involved in their services, and their voices should be heard. A rollout of targeted engagement programmes would provide a way of reaching them.

The detail:

ICS area data packs

Go

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.